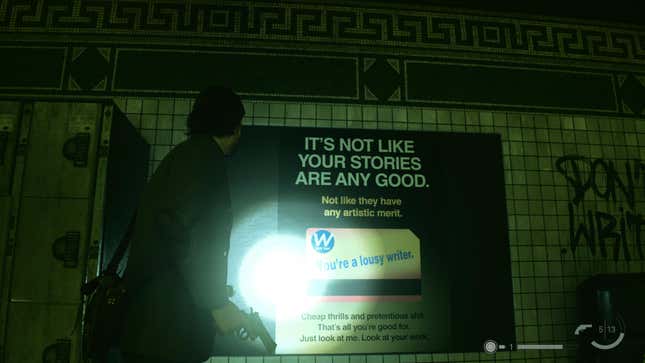

I put off writing this Alan Wake 2 review because I was scared. Scared that I’d look into myself and find I wasn’t up to the task, that I lacked the right words, with nothing to offer but emptiness and failure. It’s not at all uncommon, though, for writers to be wracked with doubt. Many years ago, I saw the novelist William Gibson give a talk in which he said that, at some point in the writing of every novel, he tells his wife he thinks it’s the worst book anyone’s ever written.

Alan Wake 2, the striking new narrative-driven horror game from Remedy Entertainment, understands this fear so many writers and other creative people face well, and uses it as the seed of frightful inspiration for its surreal horror odyssey.

Drawing you into the saga

Alan Wake 2 may be about creative doubt and struggle, but the game itself oozes confidence, a rare trait in modern big-budget games. 2010’s Alan Wake ended with a cliffhanger that saw its novelist protagonist become trapped in a shadow realm called The Dark Place, and fans have been eagerly awaiting a full-fledged continuation of his story ever since. Nevertheless, Alan Wake 2 makes its players wait just a bit longer, beginning with new characters and building its narrative tension at a tantalizingly deliberate pace.

Initially, our leading man is nowhere to be seen, as we instead follow Saga Anderson, an FBI agent sent to Bright Falls, Washington, the first game’s setting, to investigate a series of murders. Alan Wake 2 has been billed as a horror game, and it certainly is that, but it dares to start out feeling more like a gloomy, Scandinavian police procedural, with a grisly crime at its center and a few coffee-gulping cops committed to solving it.

And though the game takes its delicious time in revealing just how this is all connected to the plight of Alan Wake, there are some details that immediately make us feel Wake’s presence, even in his absence. Bright Falls has changed little since we saw it in 2010. More intriguingly, Saga’s partner is named Alex Casey, just like the protagonist of Wake’s books. He also, by no mere coincidence, has the face of Remedy creative director Sam Lake and the voice of actor James McCaffrey, just like Remedy’s first superstar protagonist, Max Payne. This isn’t just a throwaway detail, a fun little reference for the fans; it eventually becomes central to everything that Alan Wake 2 is doing.

Games of this size and scope are made by hundreds of people, and I would never want to diminish the impact they all have in the collaborative process and the final product. Acknowledging that doesn’t change the fact that Alan Wake 2, to its credit, feels distinctly authored. By that, I mean it has a specific creative impulse on which it does not compromise. Sam Lake didn’t write it alone and he didn’t direct it alone, but it’s clear that those who collaborated with him on the project were working in support of realizing his vision, at least for its narrative. Alan Wake is a writer who struggled creatively after trying to move away from the familiarity and success of his Alex Casey books. Alex Casey looks and sounds exactly like Sam Lake’s creation, Max Payne. Did Sam Lake similarly struggle in the period after Max Payne 2?

Read More: Alan Wake Creator Says Sequel Is ‘More Intense, More Brutal’

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how much autobiography went into the story of Alan Wake or its sequel. What matters is that this game has the freedom to be unabashedly itself, that it can feature a 15-minute, live-action art house film at one point—a film created just for the game—and that nobody at Remedy or anywhere else said “Let’s cut that to save money” or “Let’s make this story more conventional and easy to understand.” Or, if they did, they were overruled, leaving Alan Wake 2 free to fascinate and puzzle us with its many narrative layers and details that offer no easy explanations. It’s thrilling, in a time when games generally play it safe and offer up stories designed to satisfy in traditional ways, to encounter one so fully committed to its own vision.

Keeping the darkness at bay

And make no mistake: while Alan Wake 2 is a game that you play, it’s also every bit as concerned with storytelling as some games by that other big-budget narrative auteur, Hideo Kojima. This means that, yes, there are occasionally some substantial cutscenes to watch, though they’re always excellent and often make exceptional use of live action. However, Alan Wake 2 also finds other, more active ways to involve you in its story.

As Saga Anderson, you’ll frequently retreat into your “mind place”—Saga’s version of the mind palace technique—to make sense of new evidence and to profile key people you’ve encountered. It’s not difficult, taking the facts Saga’s gathered and assembling them on a wall where she connects them with strands of red thread, but it has the added benefit of giving you a clear visual representation of the game’s sometimes-complex mysteries, and before all is said and done, the mind place gets used in ways that offer greater insight into Saga as a person as well. It’s a fairly minor thing, but it speaks to Remedy’s desire to find new ways to engage you in Alan Wake 2’s narrative, rather than just letting gameplay be dominated by combat and having all the detective work take place during cutscenes.

If anything, combat is less prominent here than it was in the original Alan Wake, which was more of a pure action game about a horror story than an actual horror game itself. But the combat here, when it does happen, is much more intense. As Saga, you sometimes encounter Taken—the same sorts of people corrupted by dark energy that Wake fought in the first game—but now they’re much more varied, fast, and aggressive. Encountering two or three Taken in some overgrown section of the woods always feels threatening, as some may dash away from you to fling axes from a distance while heftier bruisers close in for melee attacks, all while you desperately try to maintain some awareness of their positions as they sometimes disappear into the dense foliage or the dark of night.

As in Alan Wake, you still have to burn off an enemy’s shield of dark energy with your flashlight before you can wound it, but even that feels more impactful here. The focused light causes the shield to give off sparks like a Fourth of July firework before it finally explodes with a satisfying pop. And your guns feel and sound powerful, but the Taken feel more powerful still. You will know the experience of emptying bullet after bullet into an aggressively approaching Taken, hoping to god he goes down before he gets close enough to hurt you.

It’s pulse pounding stuff, at least when it’s used to periodically punctuate your explorations and make the world around you feel dangerous. At one point, Alan Wake 2 pits you against a massive horde of Taken and tasks you with surviving for several minutes, and the combat just isn’t fine-tuned enough to support this kind of challenge in a satisfying way, but that’s a minor critique in the face of the game’s overall excellence.

Phantom Payne

But what of Alan, the game’s namesake and other protagonist? He has now been trapped in the Dark Place for 13 years, the same length of time that’s passed between the first game and its sequel. For him, the Dark Place is currently taking the form of a dark, grungy, neon-lit New York City, and he is plagued not by Taken but by Shadows. While the Taken frighten you with deranged shrieks, Shadows get inside your head with menacing whispers, but fighting them is much the same as taking on Saga’s enemies. The Shadows are accompanied by an impressive visual effect, however; a seeming bending of reality around them, and often you may shine your flashlight on a Shadow only to have it evaporate into nothingness. This only makes crowds of them more unsettling—which ones are truly just substanceless shadows, and which are the real threats?

We find Wake desperately trying to write himself out of the Dark Place. These efforts take him all over his compact but dense version of New York, in which he frequently encounters echoes of his own troublesome protagonist, Alex Casey. And here, unlike in Saga’s world, Casey isn’t a tough-talking FBI agent who just happens to look and sound like Max Payne. He clearly is Max Payne, in all but name.

The New York we see here is effectively the same noir-ish, crime-ridden version of the city the detective inhabits in Remedy’s two Max Payne games, and Payne speaks in the same heightened language, like a philosopher-poet of the world’s dark places. Casey’s prominence here is thrilling, not just because it’s great to once again hear James McAffrey spouting such hard-boiled dialogue, but because it makes Alan Wake 2’s own concerns with creativity and feeling trapped that much richer. Casey is a character that Wake just can’t seem to get away from, and perhaps Lake can’t get away from Payne, either. Perhaps he doesn’t want to.

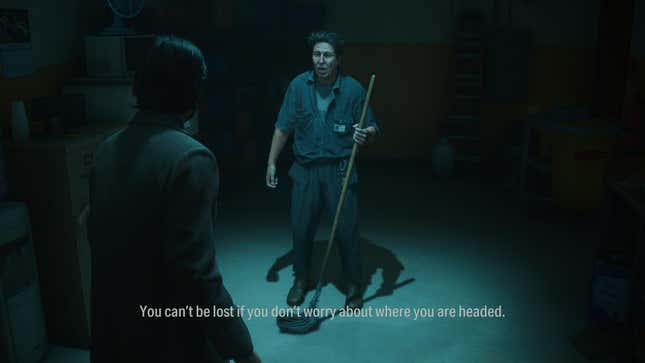

Just as Saga retreats into her mind place to try to solve problems and find a way forward, Wake has his writer’s room, a place where different locations he discovers can be paired with different plot elements to alter them, sometimes revealing vital information or creating a new path forward.

For instance, at one point you explore a hotel, trying to find a spot where a grisly murder has taken place. As you explore the hotel, you can encounter echoes of Alex Casey investigating the crime, and at one point, someone Casey is interrogating mentions “the devil.” This then becomes a concept you can apply to key locations back in the writer’s room, and it’s always interesting seeing how the space changes around you to reflect the new narrative thread Wake is working with. It’s also more open-ended and playful than Saga’s mind place, as creative writing should be. There, you can only put things precisely where they belong. Here, there aren’t “wrong” combinations, and you can try combining concepts with locations just to see what the results look like.

The struggles of writing are very difficult to dramatize, since it’s usually something one does alone, silently, staring at a screen or a sheet of paper. I won’t pretend this writer’s room mechanic successfully captures anything about the writing process or the difficulty of effectively getting ideas down on the page, but I nevertheless appreciated that there’s a gameplay mechanic here meant to simulate a writer throwing different ideas against the wall to see what sticks. It’s just another one of the many things Alan Wake 2 does that make it feel like a true original in the big-budget space.

There are also a few environmental puzzles you have to solve as Wake by using a lamp to collect illumination from certain light sources and transfer it to others—these are sometimes more fussy than fun. But it’s hard to stay frustrated at such foibles for long when the environments you’re exploring are so stunning. Whether you’re in the Pacific Northwest with Saga or the nightmare New York with Alan, the atmosphere is truly remarkable. The forests you traverse as Saga have the most convincing and stunning foliage I’ve ever seen in a game, their lush density both breathtaking and, at times, threatening. Meanwhile, Sam Lake has cited ‘70s films like Taxi Driver as a reference for the lurid NYC Alan is trapped in, and indeed, you can practically smell the rot and fear in the air on its seamy streets.

Light in the dark

But this, all of this, is in service of the story Alan Wake 2 is telling, and it’s the bold, exhilarating way it tells that story that elevates Alan Wake 2 from a fine game to an unforgettable one. Crucial to that narrative impact is the aforementioned use of live action. Remedy has long been interested in incorporating live action into its games, but it demonstrates new command of the medium here, with gameplay sometimes seamlessly transitioning into live-action, or co-existing alongside it at others. In lesser hands, such a juxtaposition might have made the gameplay feel less real, unable to stand up alongside its live-action counterpart. But here, it all feels of a piece, just shifting layers of reality that combine to make a whole.

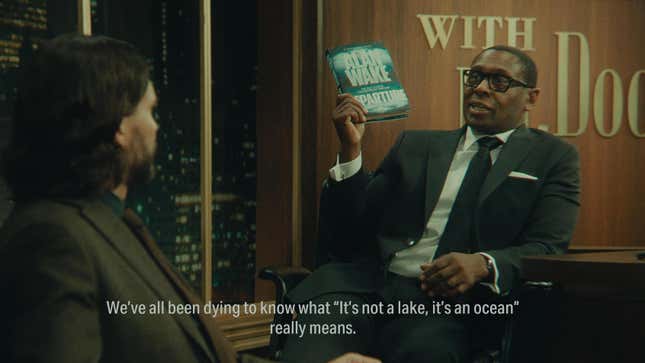

It’s hard to talk much about what happens in Alan Wake 2, both because the story is best experienced for yourself and because it operates on a foundation of dream logic. What I can say is that its narrative adventurousness is frequently thrilling, as it blends genres and modes of storytelling in ways that bring its concerns with the scary things inside ourselves into sharper and sharper focus. Particularly excellent are a number of scenes that take place on a talk show in the Dark Place, hosted by a man named Warlin Door, a fascinating newcomer to the Remedy-verse who clearly has an agenda of his own.

Door is played wonderfully by the accomplished actor David Harewood, and in the conversations between him and Wake are moments that ring true about writing and creativity. At one point, Door asks Wake how he feels about film adaptations of his Alex Casey books, and Wake says that he thinks of them as something separate from his books, works that have sometimes made creative choices he wouldn’t have. “I feel protective about my stories,” he admits, and that’s a feeling many writers can relate to. (One wonders if Sam Lake has ever bristled at creative choices others have made about Max Payne, for instance.)

Wake remains a fascinating protagonist, prickly and sometimes unlikeable, which only makes him feel more human and authentic. Saga holds her own, balancing Wake’s ego and attitude out with warmth, though she is not without her own demons to overcome. But it’s all the strange, personal, uncompromising moments in the story that really make the game sing with a distinct and singular creative energy. In a review of the new film All of Us Strangers, my friend, the film critic Walter Chaw, observes that art actually becomes more deeply relatable and more universal as it becomes more personal. “The miracle of being human,” he writes, “is the more you flay your chest, lay it bare to muscle, then sinew, then bone, exposing your heart fluttering there in its cage, the more familiar your humiliation becomes. The only universal is the personal.”

Alan Wake 2 is hardly some flawless masterpiece. It sometimes overindulges in easy jump scares, and while its narrative highs are very high, the momentum also flags from time to time. But I’d argue that it’s a game in which even the flaws contribute to its texture as a fresh and original experience, not a focus-tested product but a work that has a vision and really goes for it. You don’t need to be a writer for the struggles that Alan Wake and Saga Anderson face here to resonate with you. You just need to be a person who has ever looked inside yourself and faced doubt, fear, some deep uncertainty about your own value or your ability to handle the challenges ahead. And then done it anyway.