Batman: Arkham Knight spins one of the most ambitious video game stories ever told, and watching it thunder to its conclusion is like watching a 747 successfully land on a helicopter pad. It may not be known for its narrative, but that is its achievement—a spiraling and notably interactive tale that takes you inside the mind of one of popular culture’s most enduring and fascinating figures.

Originally released in 2015, Arkham Knight told a dark story, even by Batman standards. The Arkham games, as envisioned by the men and women of the UK games studio Rocksteady, had always provided grittier, more “adult” material than your average episode of The Animated Series. But even in that context, Arkham Knight seemed different from its Rocksteady predecessors. This Batman was angry and dangerous. He pounded through Gotham in a tank, running down unarmed looters and torturing people to get what he wanted. He grunted and grimaced; he glowered and roared.

When I first played the game shortly after it came out, that darkness pushed me away. There was an ugliness to this Batman that I couldn’t reconcile with my view of the character. A year later, armed with the knowledge of how the story ends, I replayed Arkham Knight in its entirety and it all made a lot more sense. This Batman is a different man from the hero of the first two games. His mind is not his own. His worst enemy is inside him, dying to burst out. Time is running low, and when the hourglass runs dry, he’ll become the killer he’s always suspected he might be. It’s up to us to guide him through this latest longest night of his life. Some darkness is to be expected.

Released after more than a year of teases, previews and general-purpose hype, Arkham Knight was set to be the crown jewel of Rocksteady’s acclaimed Arkham trilogy and one of the first definitive technical showcases of the then-newish console generation. But in the weeks and even months following its release, the conversation surrounding it focused on a few less high-minded things: The PS4 and Xbox One versions ran well, but the PC version was a buggy mess. The drivable Batmobile changed the series formula in a way some people didn’t care for. And the spoilers, oh, the spoilers! We had to avoid discussing the contents of the story, lest we spoil the surprises for those who hadn’t played.

Today, those concerns are mostly moot. The PC version was pulled from sale and overhauled, and while it still has lingering issues, it mostly runs fine. The hullabaloo over the Batmobile died down. And concern over spoilers has pulled a reverse-Ozymandias, washed away by the ravages of time. Look on the entirety of my story, ye Mighty, and rejoice!

All of which is to say that this re-review will not focus on Arkham Knight’s technical performance, will not dwell on the Batmobile, and will feature thorough spoilers for the entire story from beginning to end.

Batman spends Arkham Knight trapped in a triangle of villainy that allows the game to thoroughly, exuberantly illuminate the shadowed corners of his psyche. To fully understand what happens over the course of the story, you’ll have to be familiar with the events of the first two games in the Arkham trilogy: 2009’s Arkham Asylum and 2011’s Arkham City. You’ll also have to be prepared to machete your way through a narrative thick with vines of contrivance and logical contortions. Make it through to the other side and you’ll find four main characters contrapuntally arranged in a clearing, set to tell a single story in the same city on the same night. The resulting showdown is dynamite.

For the first act of Arkham Knight, Batman knows something we don’t. We see that he has Robin toiling away on a science project in a repurposed movie studio, and we know that the project is important enough that Batman repeatedly waves off his sidekick’s assistance in what would otherwise be an all-hands-on-deck catastrophe. Scarecrow is threatening to detonate a biological weapon that will kill countless people and destroy the eastern seaboard. He’s enlisted an army of mercenaries and taken over Gotham City, aided by a mysterious supersoldier who calls himself the Arkham Knight. The police are bunkered up in their station, chaos rules the streets, and it’s open season for supervillains and serial killers alike. In the face of this—and over Robin’s protests—Batman tells his protége to stay inside and focus on his research. Must be a pretty important science project.

My second time through, I already knew what Robin was up to. Midway through Arkham City, the Joker performed a forced blood transfusion on Batman, infecting his nemesis with blood corrupted by the Titan supersoldier formula he had imbibed at the end of Arkham Asylum. Batman spent most of Arkham City in pursuit of an antidote for the toxin, which was killing both him and the Joker. In that game’s finale, Batman was able to take a partial antidote, saving his own life. The Joker died. Somewhere between Arkham City and Arkham Knight, the Joker’s blood was shipped off to hospitals and infected a handful of civilians, each of whom begins to display signs of the Joker’s mania and even his personality. Batman has gathered them in Gotham to study and possibly save them. He’s also learned that, because he didn’t take a full dose of the antidote, the Joker’s diseased blood has been gradually corrupting his mind and taking him over from the inside.

Yes, this story development is ridiculous. It is grandiose and “comic booky” and whatever other pejorative you wish to attach to it. But as a means to an end, it’s also effective. Batman’s funhouse-mirror bond with the Joker has always been one of the most compelling and well-worn tropes in the Batman canon. What better way to explore that relationship than by literally placing the Joker inside Batman’s head? And if a game is going to have this much fun fighting a war within the Caped Crusader’s mind, does it really matter how we get there?

Arkham Knight’s primary conflict is between Batman and the Joker, which can be read both as a literal conflict between the hero and the biological echo of his nemesis, or as a more metaphorical conflict between Batman and the darker aspects of his own nature. This inner conflict manifests itself as the Joker, voiced by Mark Hamill, regularly appearing out of thin air and chatting with Batman, joking around and providing commentary on what his corporeal nemesis is up to. He might be dead, but that hasn’t quieted him down one bit, and as the hour grows later, he bubbles closer and closer to the surface.

The Joker’s goal is to be born again through Batman, destroying Bruce Wayne and rising anew as Gotham’s dark destroyer. He’s aided in his quest by Scarecrow and the Arkham Knight, even if they don’t realize it. They make for an effective support team: the former is a man capable of making Batman’s greatest fears manifest; the latter a literal, Joker-created manifestation of those fears.

Scarecrow’s goal is to break Batman down and expose him to the world as a frightened, ordinary man. In pursuing that goal, he unknowingly sets the stage for Batman’s ultimate showdown with the Joker, even though that showdown takes place within Batman’s psyche and Scarecrow never actually knows it’s happening. Batman’s greatest fear, which Scarecrow hopes to expose, is that he’ll succumb to the darkness he knows is inside of him. The people he cares about—Dick Grayson, Tim Drake, Barbara and Jim Gordon—will suffer and die, along with the innocent populace of Gotham. Scarecrow makes for an ideal supporting villain and a useful narrative device. He can bring the Joker “out” in a variety of ways, and over the course of Arkham Knight, he does just that.

The Arkham Knight, a violent, armored soldier with a secret origin, is often maligned by critics and fans but is no less crucial a part of the story. He’s not just a convenient way for the game to introduce an army of gun-toting goons for Batman to fight (though he certainly is that). He’s also the flip side of the Scarecrow’s narrative coin. The Knight is eventually revealed to be a fallen Robin named Jason Todd. Jason was believed to have been killed by the Joker, when in truth, the Joker tortured and brainwashed him until he blamed Batman for his suffering and became bent on revenge. The Arkham Knight is a personification of Batman’s greatest failure, come back to haunt him.

In the run-up to Arkham Knight’s release, it seemed like there would be two primary villains: Scarecrow and the mysterious Arkham Knight. The truth was more complicated. Arkham Knight hinges on the intersection of four characters: the Joker, Scarecrow, the Arkham Knight, and Batman. The Joker is the central villain, and his goal isn’t control over Gotham—it’s control over Batman. Scarecrow and Jason Todd are both unwitting accomplices to the Joker’s plan. Batman is haunted by the people he failed to save, but in order to come through this trial alive, he must learn to allow his friends to risk their lives to help him. His goal isn’t to save Gotham, it’s to save himself.

Like any video game series that makes it to three entries under the same developer, there comes a point where things risk becoming too elaborate for their own good. It’s equally true of the plot and of the gameplay, and both Arkham Knight’s story and gameplay systems occasionally buckle under the accumulated cruft of years of iteration and elaboration. When it comes to the marriage of the two things, however—the places where the story expresses itself through interaction—Rocksteady is working on a level that most of their big-budget competitors can’t touch.

Arkham Knight’s major and minor story developments are almost always playable, and rarely spool out as a non-interactive cutscenes. That begins early in the story, when Batman chooses to sacrifice himself as in order to save the city from Scarecrow’s fear gas. You, the player, must manually relocate each tube of the deadly toxin, all while Alfred pleads with you over your radio to escape while you still can. Later, when Batman must brave the streets of a fear-gassed Gotham in order to install a new power cell on the Batmobile, the introductory sequence repeats. A long night just keeps getting longer, and you must urge Batman forward even as his immune system starts to break down.

An interactive story like this wouldn’t work half as well without Rocksteady’s brilliant cinematography and stagecraft. Arkham Knight’s camera is practically a character unto itself, particularly in the moments when it briefly breaks free of your control in order to more dramatically portray what’s happening on screen. It swoops and spirals, grandly framing the action on-screen. When Batman ejects from the Batmobile, he bursts into the air, the camera catapulting up behind him. When he dives toward the earth, the lens stretches, perfectly conveying drop-speeds he never actually achieves. This game moves beautifully.

Through careful staging and camera trickery, Arkham Knight enlists you, the player, to be both camera operator and leading man. Because you’re usually given control over which way the camera is pointing, the directors have come up with all manner of creative tricks to redirect your eye and surprise you. The Joker’s first appearance is a kick, with him popping into view as Batman finally vents the last of Scarecrow’s gas tanks. I’ve lamented how many of us struggled to even mention his presence in the game in the weeks after it came out, but I understand why Rocksteady wanted to keep it a surprise. I still remember my shock at seeing him smiling at me, pistol in hand.

Joker’s subsequent appearances are woven more seamlessly into your travels through Gotham. He always appears in the place you weren’t looking: One minute you’re alone, then you turn around and there he is. You’ll grapple up to a rooftop only to find him standing there, ruminating on your decisions while taking in the view. The Joker becomes the nagging voice that Batman can’t quite escape, however stoically he may ignore it. When Batman finally cracks and attacks the Joker, it’s a breaking point that the game has been carefully building toward for hours.

Those sorts of creative, interactive flourishes carry over into the strong side missions, many of which subtly echo the central themes of identity and duality. In one mission, you’re put in control of Hush, a Bruce Wayne doppelgänger whose storyline actually began in Arkham City. In another, you control Azrael, a man training to take over for Batman should he ever retire. Hush has Bruce Wayne’s face and Azrael has Batman’s moves, and both let us see our hero from a different perspective.

Another quality side mission has you tracking Man-Bat (!!) across Gotham, gradually uncovering the tragic tale of another man whose delusions of grandeur hurt the people he hoped to protect. The Man-Bat’s first appearance also happens to be one of the best video game jump-scares I’ve ever experienced, and later, the Joker perfectly re-enacts the scare before collapsing in gleeful hysterics. I yelled, loudly, both times.

Then there are the puzzles. Some are essential components of the story while others are optional, but each provides a thoughtful caesura from the narrative’s bleak forward march. Clever puzzle solving has long been a crucial part of the Arkham formula, and Arkham Knight is laced throughout with head-scratchers that wouldn’t feel out of place in a Zelda game. At any given moment you may be asked to hack your way around a battalion of tanks, or figure out how to get an electrified batarang through an inaccessible opening, or plug into a blimp’s navigational tools and rearrange massive shipping containers by tilting the whole airship on its side.

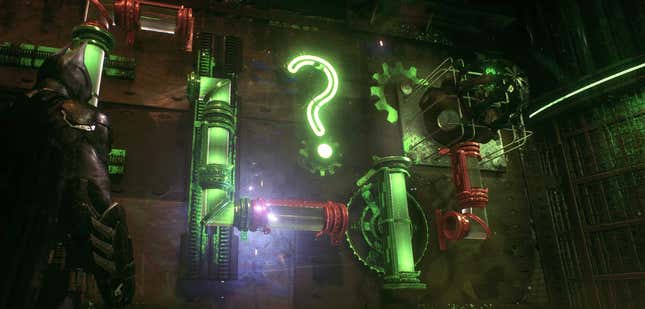

The dozens of optional Riddler puzzles strewn around Gotham are often the most rewarding challenges of the bunch, numerous and well-considered enough to be the sole focus of a less sprawling game. Each one requires some sort of lateral thinking or creative puzzle solving, along with patience and possibly some knowledge of Batman lore. I have not solved them all, and I doubt I ever will. I appreciate just knowing that they’re there, waiting for me, should I ever feel the urge.

For all my talk of groundbreaking interactive narrative and superb puzzle design, most of the player’s actions in Batman games involve some combination of: punch, kick, flying elbow, batarang. Rocksteady appears to have had a fine old time elaborating on their basic melee combat over the eight or so years they’ve spent making Batman games. It’s a system we’ve seen mimicked in countless games from Sleeping Dogs to Shadow of Mordor, and that’s for good reason: It works.

Things started simple in Arkham Asylum—when a guy is about to attack you, press Y to counter. If you’re on the offensive, press X to attack. If you want to dodge, double-tap A. By the time Arkham Knight rolled around, the number of combat variables had increased substantially. There are electrified enemies who you can’t punch. There are medics who pull injured enemies back from the brink. There are towering heavies who require a focused flurry of punches to take down. There are ninjas you have to dodge multiple times, and there are gun lockers that can turn a regular grunt into a deadly threat. Batman’s toolkit has expanded as well—you can shock or freeze enemies, launch special batarang combos to K.O. downed foes, snatch guns out of your opponents’ hands with a grappling hook, leave tripmines strewn across the battlefield, and even occasionally tag-team with the Batmobile to skeet-shoot your opponents out of the air.

The same geometric growth has been applied to stealth sections—there are enemies with remote drones, jamming devices, electronic sniffers, and huge beefy guys with miniguns who take ages (and a lot of noisy punches) to take out. To counter all that, Batman has got an upgraded hacking device, a nifty tool that can project voices around the room to distract and redirect enemies, and the ability to quickly change floors by hoisting his body through vertical vents, among other things.

This added complexity isn’t always beneficial to the game, and the layered gadgets and counter-gadgets can be a lot for even the most seasoned Bat-veteran to keep straight. There are balance issues as well—if you can take out every goon with the same combination of two or three moves, are those other ten gadget combos really necessary? There are spots in Arkham Knight where the designers seem unable to counter Batman’s most powerful abilities. A mildly capable combatant should be able to survive even the most overwhelming enemy force, and by pressing the A button repeatedly, you can simply hop around most brawls without being touched.

New Game+, the more difficult mode you can play after completing the game, comes closer to balancing things out. The enemies are pumped up from the get-go, armed with the most deadly tools and weapons. Players are given fewer on-screen combat notifications, which does a surprising amount to shake up the fistfights and keep things exciting. However, the real test of Arkham Knight’s teetering pile of enemies and abilities comes in the included “AR Challenges,” which double as leaderboard time trials and give you all sorts of specific challenges to complete. You haven’t fully explored Batman’s move-set until you’ve attempted to perfectly line up three goons for a three-way line-launcher takedown, or tried to clear a room of gun-toting heavies in less than a minute.

If you think you’ve mastered Batman’s many techniques and gadgets, you can disabuse yourself of that notion by browsing YouTube and looking for AR Challenge speedrun videos. Here, watch a player set up a 13-second takedown so perfectly executed that it manages to end on an exploding-gun punchline:

In the months since it came out, players have stress-tested Arkham Knight to the utmost, often with impressive results. We mere mortals can only admire from afar. It’s pleasing to know that the game’s combat and stealth systems can support play on this high a level, even as they are responsive and satisfying enough for normals to have a good time, too. Punch, kick, flying elbow, batarang—these actions were just as fun the hundredth time I did them as they were the first.

The most interesting parts of Arkham Knight story take place between Batman’s pointy ears, and it’s too bad that Rocksteady couldn’t have done more with the city of Gotham itself. Arkham Knight is the first of the main trilogy to allow Batman to explore Gotham proper—Asylum was set entirely at that island institution, and City was quarantined within a district of the city that had been converted into an urban prison. For all its empty shops and boulevards, the evacuated Gotham of Arkham Knight might as well just be another prison, devoid as it is of civilian life or any meaningful indication of what it looks like when hell isn’t breaking loose. As critic Austin Walker wrote back when the game came out, “I want a Batman game where I’m compelled to save the day not because of abstract threats, damsels in distress, or a desire for personal vengeance, but because the beauty of Gotham City compels me to protect it. Instead, I’m left for the fourth time with Batman and his playground.”

But Batman stories have long explored complex inner conflict alongside obvious real-world derring-do, and while Arkham Knight’s outer world may not be particularly inspiring, its inner worlds are richly detailed and ripe for character development. The game does great justice in particular to its central villain, despite the fact that he may be nothing more than a figment of the protagonist’s imagination. It seemed every time I spun the camera the Joker was there, waiting for me on a rooftop, leaning against the wall with unasked-for council. Through his taunts I came to understand his insecurities, his desperate need for validation, his dreams and his darkest fears.

This Joker doth protest too much, and Rocksteady’s writers explore his psyche with such exhausting single-mindedness that the relative simplicity of some of the other villains comes as a relief. When I needed a break from the main storyline’s oppressive psychological spelunking expedition, I’d go thwart one of Two-Face’s bank robbery schemes or work with Nightwing to stop the Penguin’s weapons deals. Arkham Knight’s narrative is so tightly constructed and intense that it’s nice to take a breather every now and then.

As Batman creeps through his city, you’ll overhear a seemingly endless collection of radio conversations between various rank-and-file goons, many of whom actually seem like decent fellows. They’ll complain about their bosses, put on shows of insecure braggadocio, and trade war stories about events from previous games. A couple of guys might groan about how their significant others don’t understand their mercenary lifestyle. A different pair debate the morality of what they’re doing, salivating for an imagined payday that even they acknowledge may never arrive. After Scarecrow reveals Bruce Wayne’s identity, you’ll hear Gotham’s thugs express their disbelief. Some of them sound vaguely crestfallen, like little kids who’ve learned that Santa is just a mall employee in a fake beard. They might be bad men who do bad things, but they admire the Caped Crusader just as much as anyone else. One guy even explains how Batman inspired him to join the military and serve. He notes the irony that all these years later, he’s on the other side.

It doesn’t take long to begin to sympathize with these dopes, which can make it oddly uncomfortable to watch Batman carve through them like a weed-whacker through so much dried grass. You’ll slam into guys on the street with the monster-truck wheels of the Batmobile, electrocuting them and sending them flying twenty feet through the air. You’ll pelt them with rubber tank-bullets strong enough to immediately knock them out. You’ll torture them for information, then brutally bash them unconscious and toss them away like trash. Maybe that was the guy who just wanted his husband to support his professional goals, you know? Maybe that was the guy who secretly thinks Batman is amazing.

During one memorable sequence early in the game, Batman pins a guy under the Batmobile’s spinning rear wheel and demands information. As the man squeals and protests, you’re given the prompt to rev the engine and spin the wheel as Batman backs it closer to the man’s face. It’s a pretty hardcore move even for Batman, and the first time I played it, it turned me off. When did Batman become such a jackbooted Jack Bauer?

As I replayed the game and arrived at that sequence, I stopped and considered what was really going on. Many video game power-fantasies beg us to let them have it both ways. In order to have a good time playing as Gotham’s all-powerful protector, we must accept that his use of force is justified and his mission is noble, even though we’re basically just role-playing a rich dude who makes himself feel better by beating up lowlife crooks and the mentally disturbed. Arkham Knight can’t fully square that circle, but it does cleverly sidle up to the problem by suggesting that Batman knows he’s going too far. His mission, in the end, is to retire the cowl and fake his own death. He’s terrified of what he’s becoming and he wants to stop.

If Batman’s actions in Arkham Knight don’t seem like the even-handed, wry hero we came to know over the course of the first couple games, it’s because they’re not. This is a haunted, poisoned man, fighting to maintain control over his own mind. He’s slowly turning into his nemesis, and his violent outbursts only grow more unhinged and dangerous as the story progresses. Batman might not place an unarmed man under his tank treads, but the Joker would.

Far more so than in previous games in the series, Arkham Knight revolves around Batman’s friends and partnerships. Throughout his long night in Gotham, almost every one of Batman’s relationships is put to the test. Nightwing comes in from out of town to help take down the Penguin, and in the process demonstrates his independence despite his former mentor’s warnings and concerns. Meanwhile, Batman is keeping his new Robin, Tim Drake, out of harm’s way under the pretenses of having him study the infected Joker victims. It becomes clear over the course of the game, however, that he’s also terrified of losing another protége in the field. Catwoman is forced to work with Batman to deactivate a bomb the Riddler has locked around her throat, but as they work together in their usual uneasy alliance, their banter betrays how much they enjoy one another’s company. Even Batman’s own car is a constant companion, helping him solve puzzles and bailing him out of more than a few jams before eventually sacrificing itself for him.

Arkham Knight mechanically expresses Batman’s reliance on his allies in a number of ways. There are stealth sections, such as when Batman and Robin must work together to take down a room of armed thugs or Batman needs to distract an unhinged, singing Joker acolyte while Robin disarms bombs in the background. There are tag-team puzzle challenges, like when Batman and Catwoman must carefully communicate information back and forth to one another in order to survive the Riddler’s elaborate deathtraps. And there are tandem fights, where Robin, Nightwing, or Catwoman team up with the Bat to take down a room full of thugs. These fights are never particularly challenging, but they’re not meant to be—they’re a mechanical expression of how much better Batman is when his friends have his back.

Barbara and Jim Gordon play their own crucial roles in the story, bolstering and expanding our understanding of Bruce Wayne’s complicated relationships. Early in the story, Scarecrow appears to use fear gas to induce Barbara to commit suicide, and Batman spends the bulk of Arkham Knight believing that he’s gotten her killed. He’s reliving his worst nightmare—that of being powerless to save the people who risk their lives to help him—and he spends most of the game believing that Oracle has met the same fate as Jason Todd. When Jim learns that his daughter died because of Batman, he declares their alliance over and foolishly storms off to deal with Scarecrow himself.

Of course, Barbara was never dead to begin with. A fakeout or two later, we get a triumphant sequence where she, somewhat the worse for wear but very much alive and pissed off, teams up with Batman to take down an army of the Arkham Knight’s soldiers and tanks outside the Gotham police department. With a press of a button, she can tip the odds against the bad guys, hacking their drones and setting off chain reactions that make the victory a breeze. This is its own kind of victorious tandem fight. Once again Arkham Knight reminds us how much Batman needs his friends.

The supporting cast is further fleshed out over the course of several Arkham Episodes, which were originally released as piecemeal DLC over the course of 2015. The Episodes suffered for the way they were released, since each one isn’t really meaty enough to draw players back to a game they may have just finished a month prior. Taken together as a part of a finished whole, they’re much more appealing, particularly the Nightwing, Catwoman and Robin stories, each of which take place after the conclusion of Arkham Knight. They’re still inessential, and mostly just give us further opportunities to do the same sneaking and punching we’ve done so much of in the main game. But they also further enhanced my appreciation for Batman’s allies by letting me play them each on their own.

A great story usually has a great ending, and Arkham Knight’s grand finale is a stunner. After defeating the Arkham Knight and saving Jason Todd, Batman is forced to surrender to Scarecrow anyway. Scarecrow reveals Batman’s identity to all of Gotham, then injects Bruce Wayne with fear toxin on camera, hoping to show the citizens that their savior is just as terrified as the rest of them. Instead, Batman’s inner Joker gets involved, which leads to one of the best-executed finales I’ve ever seen in a game.

We begin inside Batman’s toxin-induced nightmare. The Joker has finally taken over his body and used his arsenal of advanced weaponry to wreak havoc on the city. Throughout this section, players are given Batman’s tools without the restriction of his nonlethal creed. We kill dozens of people with the Batmobile’s gatling gun, then guide the Joker as he guns down each of his supervillain competitors one by one. Gotham is burning, and the Joker is king. Then suddenly, our perspective changes. Scarecrow hits Batman with another dose, but the Joker has taken over, so it’s the Joker who absorbs the toxin. All at once we’re seeing things from his point of view. which means we’re seeing his fears.

The conquered city fades to black and the Joker plunges into his own frightened fantasy, imagining a world that has completely forgotten him. He’s standing at his own neglected grave, surrounded by statues of Batman. He attempts to destroy the statues, but is quickly overwhelmed by stone-carved versions of the man he could never defeat. He becomes lost within the nightmare, haunted by the thing he fears most: Batman. By manifesting as the Joker’s fear, Batman regains control of his mind and tricks the Joker into a cage of his own making, locking him away and recovering his sanity.

First of all: That is some crazy shit for a video game to try to pull off, particularly given that it doesn’t explicitly spell out what’s happening. Second: That is some even crazier shit for a video game to make playable, yet the majority of Arkham Knight’s final sequence is interactive.

Considering its towering ambition and many moving parts, Arkham Knight’s story resolves itself with an unusual amount of focus. Batman faces his fear of the Joker and proves once and for all that he’s stronger than his greatest enemy. Jason Todd comes to Batman’s rescue in the nick of time, once more demonstrating that Bruce Wayne is only as strong as the people he’s got in his corner. Even the Joker plays his part, inadvertently saving his greatest enemy from overdosing on fear toxin by absorbing the brunt of the second dose. Betrayed in different ways by both the Arkham Knight and the Joker, Scarecrow’s master plan unravels.

It ain’t exactly Shakespeare, and there are certainly plot holes and contrivances. Jason Todd’s introduction lacks the necessary setup to make the reveal of his identity really land, and the Scarecrow’s master plan never makes much sense on its own. The final showdown with the Arkham Knight is drawn out over too many boss battles, and those endgame Batmobile fights are a real slog. But there’s a reason so many video games fall apart in their back half—eventually, the people making the game have to make some compromises. It’s remarkable that for all the things that doubtless barely held together in the final cut, Arkham Knight’s ending manages to tie three games’ worth of plot into a ludicrous but satisfying finale.

When you die in an Arkham game, you’ll have to sit through one last taunt from the villain who defeated you. They loom over your body, presumably watching as the life drains from your eyes. Two-Face might lament that you couldn’t come around to his way of thinking, or the Penguin might order his boys to take your mask and string up your body. Arkham Knight continues that tradition, with a notable twist: sometimes, the Joker will come out and talk to you. Instead of expressing glee at your demise, he’s panicked and upset.

The Joker has lost his last chance at resurrection, but he also just seems sad that his old nemesis is gone. Given what we’ve come to understand about him over the course of the game, it makes sense. His relationship with the Bat has always had a dash of romance, and the love story is finally over. Even in death, the Joker needs Batman to feel alive. If his plan to conquer his foe’s mind had come to fruition, he probably would’ve been miserable.

After defeating the Scarecrow and locking up the rest of the villains terrorizing the city, a now-unmasked Batman activates something called the Knightfall protocol and vanishes, faking Bruce Wayne’s death in the process. The circle closes, but it forms the dot of a question mark. Is Batman really gone? Is the Joker really dead for good? Could either of these characters exist without the other, and in one’s absence, must the other disappear?

As the curtains gently billow to a close, those and other lingering questions can remain unanswered. Arkham Knight almost certainly won’t be the last great Batman video game, nor must it be. But after watching Bruce Wayne and his clown-faced nemesis wink out of existence one last time, I feel I’ve seen what I came to see. I can crinkle up my ticket stub and shrug into my winter coat, exiting the theater without a look back for whatever secrets or teases may await after the credits. It’s over. This was the story of Batman, and it was good.