Final Fantasy XVI situates itself within a backdrop of swords, sorcery, and political turmoil, as its picturesque world of Valisthea is filled with inhabitants complicit in the upholding of slavery. Throughout the land, where lush evergreen forests, dank underground ruins, and rolling dunes are common sights, magic reigns supreme. Channeled through prodigious crystalline landmarks known as Mothercrystals, magic is the cardinal resource through which all empires–personal and political, local and national–are built. Beneath the surface, a resistance slowly builds its ranks, led by a noble turned slave turned outlaw seeking to unburden the world from the crystals, and the oppressive systems of slavery their existence has enabled for so long.

Real-world inspirations for Final Fantasy XVI’s injustice

This is the backdrop against which the narrative of Final Fantasy XVI plays. It’s an alluring setup that brings into focus why the development team was interested in creating the first mainline game in franchise history to be rated Mature, one influenced by the political intrigue and grim violence of Game of Thrones. While the game certainly succeeds at evoking the high-wire, world-ending melodrama you’d expect from a Final Fantasy title, I found that it utterly fails at delivering on the promise its worldbuilding sets up in telling a nuanced tale about enslavement and resistance.

(Note that this piece discusses elements of Final Fantasy XVI in some detail.)

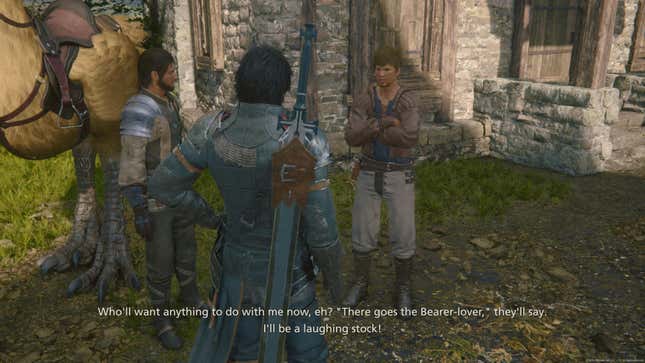

In the world of Valisthea, anyone has the random chance to be born with the ability to wield magic. These magic users are called Bearers. Unlike in many tales of fantasy, however, magic-users, by and large, aren’t the ones in power. Instead, most Bearers are “Branded,” tattooed with ghastly marks that disfigure their faces, distinguishing them from regular people and marking them as slaves.

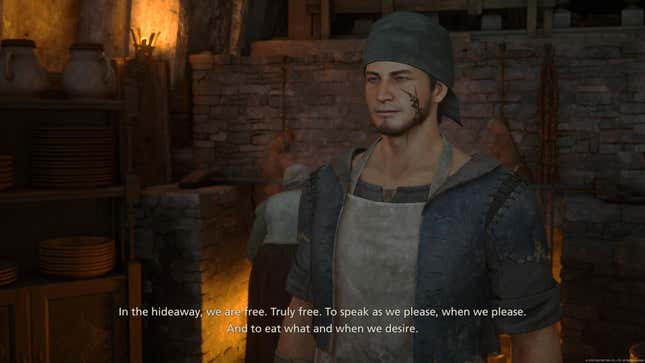

In Final Fantasy XVI’s world, humanity progressed solely through the applications magic provides, which can be drawn from fragments chipped away from the Mothercrystals scattered across the land. For instance, someone without magic ability themselves might still use a crystal to cook a meal, or conjure some fresh water. The other mode of progression is through the enslavement of Bearers who are forced to use their magical abilities until their very life force is weaned away. In Valisthea, a Blacksmith doesn’t fire their forge through flint and iron, but through crystal or the forced labor of Bearers.

From the start of the game, it’s clear that XVI’s take on slavery is inspired by real-world historical events, most notably that of Black slaves in the United States, as well as aspects of Jewish experience during World War II, with the branding of Bearers serving a similar function to that of the yellow badges Jews were forced to wear in Nazi Germany.

These are daring choices that some may find commendable. It’s clear the FF XVI team was very keen on telling a story that is interested in the human cost of resistance, the atrocities of war, and the impact of slavery. However, while the game tries desperately to show the dehumanizing nature of enslaving Bearers, there’s a hesitancy to fully explore the debilitating toll that its existence has on human life. The game is comfortable showing the violence Bearers endure, as well as the aftermath of violence, but we rarely get to see how their enslavement affects them in other, more subtle, psychological and sociological ways. A world built on mass slavery suggests a social depravity that is much greater than the physical violence showcased in the game. Unfortunately, while the enslavement of Bearers presents an intriguing backdrop for the emotional story the game sets out to tell, it’s clear its more interested in being a character study of leading man Clive Rosfield than in exploring or indicting the evils of slavery.

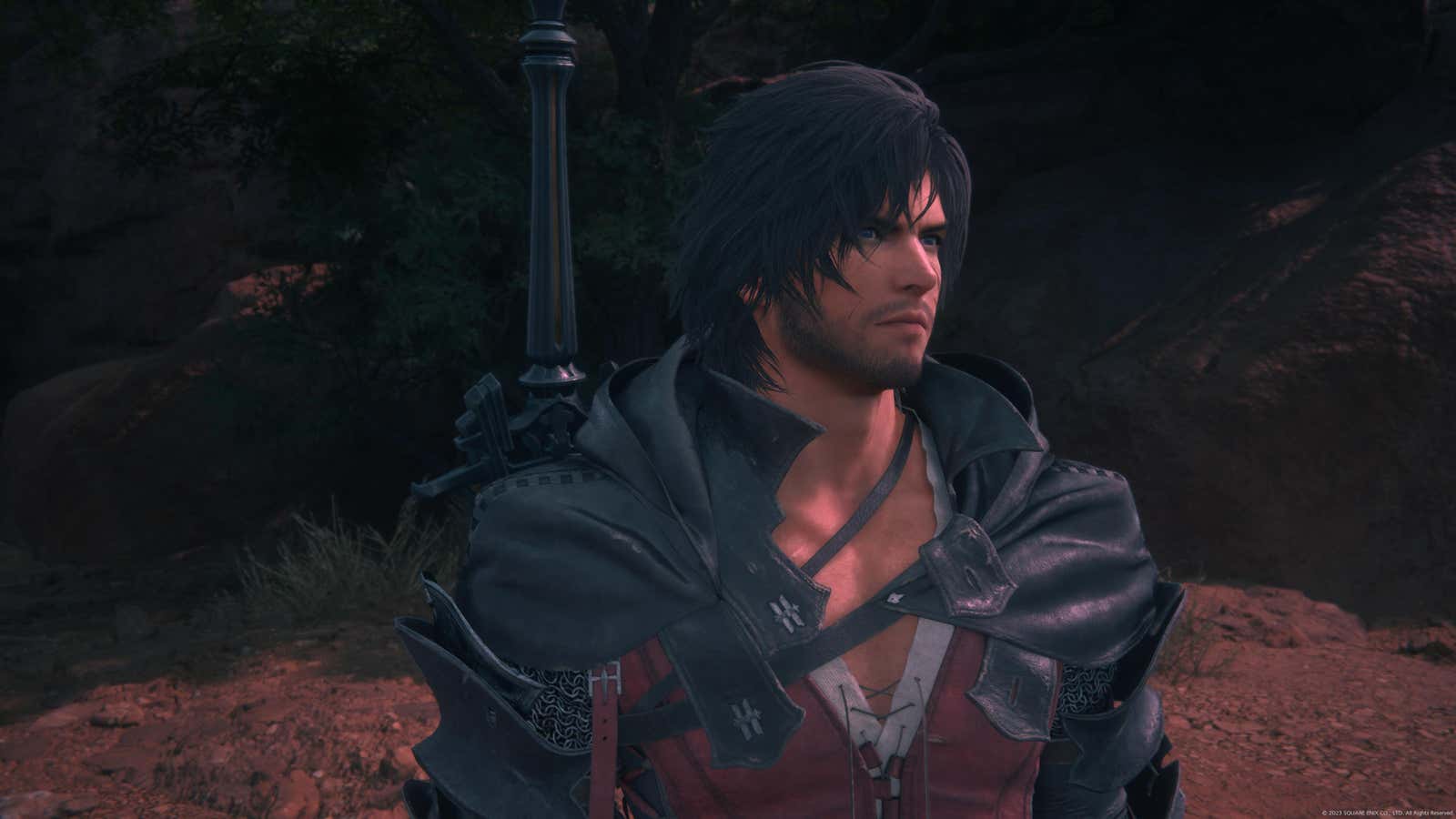

Clive: a real human being and a real hero

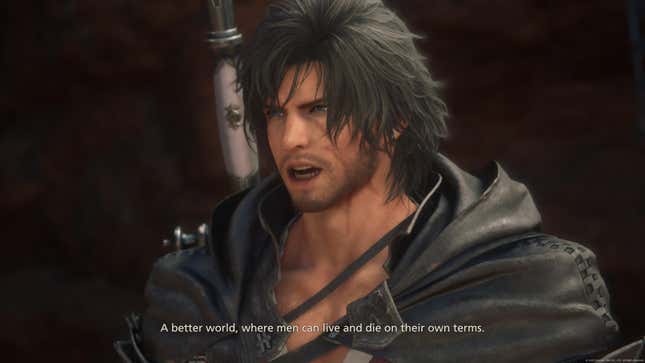

Overall, Clive is an incredibly likable and fairly well-realized character, one who shows more layers of personality and lived experience than many Final Fantasy protagonists of the past few years. But the ways in which the game situates Clive as the savior of this world feel a bit misguided. While the story is divided into three distinct eras of Clive’s life, exploring various pivotal moments that shaped him as a one-of-a-kind Bearer who is able to channel the power of any of the land’s Eikons (powerful elemental entities and this game’s version of the FF series’ traditional summons), it could be more broadly divided into two distinct narrative arcs. The first half deals with the plight of Bearers and the efforts to liberate them undertaken by Clive’s band of freedom fighters, and the latter half with the quelling of a world-ending threat that bears a personal connection to Clive and his younger brother, Joshua.

The game goes to great lengths to dress its scenes with imagery suggesting the unfair treatment of Bearers in the world. Entering settlements, you’ll find merchants scolding their Bearers. As you walk along cobblestone streets you’ll see a plethora of menial tasks that Bearers are forced to complete like keeping fish chilled, using their magic to cut hedges, keeping a forge lit for a blacksmith, and running errands between settlements for their masters. It all screams, “Look at how the Bearers are poorly treated!” All of this feels a bit like window dressing though, like entering a Disney ride filled with animatronics. Slavery on loop.

This imagery signifies to us that the Bearers have challenging lives. And while the developers were able to imagine a plethora of grounded ways in which the magic of Bearers could be exploited, they often fail to present the same level of awareness in thinking about the psychology of slavery, both on the part of the enslaved and the enslavers.

After an exceptional prologue chapter that sets up Clive and his relationship to his brother Joshua, we are brought into the middle portion of Clive’s life. It’s here that we learn he is now Branded, forced into military service under an elite squadron called the Bastards. It’s also here that it becomes clear what the story of Final Fantasy XVI is truly interested in.

While the game painstakingly imagines how a world run on magic might operate on a superficial level, the decision to omit the thirteen years of enslavement Clive experiences after his family’s kingdom was overtaken reveals the game’s refusal to look too closely at its own narrative conceit. Instead, we find Clive in this section on, unbeknownst to him, his final day of enslavement before being freed through happenstance by encountering Jill, his childhood friend, and Cid, the leader of a contingent of escaped Bearers trying to create a different world.

It’s a strange choice for a game that’s ostensibly so invested in unpacking the struggles of Bearers. Clive exists within a unique position; he is from a noble family, falls from grace into enslavement under a rival kingdom, and ultimately becomes an outlaw seeking to free the world of its chains. This is an incredibly interesting backdrop for his character. However, we never get to embody the reality of what enslavement looked like for Clive. We never get to see, psychologically, how this kind of life would impact him, both in the moment and years after. By foregoing showing us the struggles Clive experienced during his thirteen years of servitude, the game does the player a disservice, reducing what should be the source of Clive’s and the game’s moral outrage into a mere plot point players can interact with in a encyclopedia entry.

And I get it. There’s another version of this game that is incredibly pedantic, lecturing at players for hours on end, and nobody wants that. But what we get here is the game’s message being neutered to simply a bland, mild-mannered “Slavery is bad,” without the insight, anger, and conviction that could have come from more closely illuminating the experience of Clive in servitude and the economic and social systems of Valisthea that support slavery. While I wish I could say that slavery’s fundamental evil is a universal truth we all agree upon, I’m not that naive. This surface-level engagement with the lived realities and horrors of slavery results in a much less interesting story and creates a feeling that Clive–someone who has been a slave for many years–is just now coming to grips with just how dehumanizing and insidious slavery actually is.

The things Final Fantasy XVI doesn’t see

What fascinates me about the world of Valisthea, something that’s never really explored despite the numerous side quests you can undertake that touch on the lives of Bearers and their masters, is the idea of complicity that many of the “good” guys have in the plight of Bearers. While its clear from the opening hours of the game that Clive has some discomfort about the enslavement of Bearers in Rosaria, I would have loved to see more of his evolution in thinking on these subjects. There’s a resistance, too, to presenting any of the “good” guys as anything but that. The game goes to great lengths to place the player in a world that feels grounded, a world where people live complex, difficult lives, one where choosing to live–especially against the status quo—is a revolutionary choice. While this is an admirable message, I think it would be further bolstered by presenting characters like Clive within an arc that leaves room for uncertainty, mistakes, and growth.

Clive, while clearly a good person, has benefitted from the work of slaves in his youth–I’d love to have seen him ruminate a bit on that. He exists within a muddy positionality as a royal turned indentured soldier who has undoubtedly done deplorable things to stay alive. Not only was Clive a slave, but the implication of his duties during his enslavement suggest his work helped perpetuate slavery onto others. To me, that is a very emotionally resonant identity to exist within, but the game rarely plunges into the moral compromises many of us make in order to live within oppressive societal systems.

Take Clive’s father, Elwin, for instance. He is presented as heroic throughout the game, and yet as the Archduke he seemingly would have had the power to liberate the Bearers in Rosalith but he hasn’t. This creates an interesting tension for his characterization, one that hints at the much more nuanced and three-dimensional character he could have been. But by the end of the game, it’s revealed in a letter that he was trying to find an alternative. While that’s great, it also feels a bit like the game saying, “No, for real, he’s a good guy!’ When, in fact, it’s much more interesting if he’s merely a good guy to some.

Since the game maintains such a close lens around Clive’s experiences, omitting those years of his life in which he experienced slavery firsthand means that we must learn about the struggles of Bearers predominantly through side quest content that is never given the same level of care and attention that the bombastic main story quests are, especially once Ultima–the world-ending threat–is introduced midway through the game.

All of these aspects are a question of perspective and affordances, what the development team wanted to focus on and what seemed to be secondary. There are certainly some wonderful moments in the side content of the game, but by placing the majority of the storylines surrounding the experiences of the Bearers there, the game tells us that, actually, their experiences don’t matter–in fact, you can skip them all together and still understand the message we are trying to convey.

Depicting slavery in video games is a hard thing to pull off. Why? Because the reality is that boiling down slavery to it just being bad doesn’t do justice to the true magnitude of its evil. I’m not asking for the story of Final Fantasy XVI to be solely about enslavement and the freeing of slaves, but I am asking why more care wasn’t placed into this key worldbuilding element of the game. It feels like a missed opportunity. The ways XVI conveys the lived reality of Bearers living in servitude suggests a failure of understanding as to the real-world, economic machinations of chattel slavery.

Within chattel slavery, the slave is legally rendered as the personal property (or chattel) of the slave owner. Slavery is about labor and industry, it’s about capitalism and colonization. But the game’s systems aren’t equipped to actually engage with the economics involved in this aspect of slavery and how these things bleed into the overall understanding of the dehumanization these practices cause. The main verb of XVI is combat (incredibly fun combat, to be clear), and with that constraint comes a number of complications in unpacking the ideas it sets forth.

In a world where becoming a Bearer isn’t a given or even something that can be anticipated, as well as a world where not only nobility but everyone who is not a Bearer themselves has an opportunity to own slaves to do their bidding, you’d think that there would be more care provided for these people. This is especially true given the fact that resources from the Mothercrystals are depleting rapidly–especially after Clive and co. begin destroying them.The value attributed to any one Bearer would only grow as magical resources continued to disappear. By failing to acknowledge the economic drivers of slavery within society, Final Fantasy XVI’s narrative aspirations buckle under their own weight.

Defeating slavery was just training to fight God

While just about every Final Fantasy title ends up being about saving the world from a cataclysmic event, I can’t help but feel that when XVI shifts its focus to Ultima, the game begins to fall apart. Sure, the set piece Eikon battles are extraordinary (can we talk about Titan Lost and Bahamut?) but it’s all a bit disheartening how quickly the table setting in the first half around freedom and revolution gets cast aside for a pretty rote extraterrestrial villain. It feels as if the team wasn’t confident in their ability to fully unpack what they’d spent so long building.

To me, this is a failure of imagination. Creating a god-like being who threatens the livelihoods of all people in Valisthea is the easy route, but what XVI nods at from time to time without ever fully committing to it is the fact that the enslavement of Bearers is also an existential threat. One that is instantly more relatable, and also much more complimentary to Clive’s quest for vengeance, reconciliation, and a different world for all people.